Week 32 – PET scan issues and pictures

South Africa occupies the southern tip of the African continent. We pride ourselves on being more advanced than most of the rest of Africa. A few statistics culled from official publications: Two-thirds of the electricity consumed in Africa is generated in South Africa. 40% of the continent’s phones are here. 20% of the world’s gold is mined here. 84% of South African households have access to clean water. More than 70% of South Africans live in formal housing. 70% of households have electricity.

Although it is probably our most serious health issue, I won’t talk about HIV/AIDS in the South African context here. Perhaps another day…

When I was diagnosed with melanoma at the beginning of 2006, I was sent for a PET scan. At the time I didn’t know very much about it, but I quickly learned about the technology. But this did not prepare me for the actual experience, and I suddenly discovered how irrational feelings of claustrophobia could achieve a life of their own. I had to take a couple of additional tranquilizers to get through the process.

Another serious problem was the cost of the scan. This was about R12000 at the time (converts to about US $1600 at the official exchange rate). But the real challenge was that PET scans were not covered by my medical aid scheme. I could afford to pay this, but what about patients who are not so lucky?

A couple of months later, when I had come to grips with this melanoma creature, I did some more investigation into PET scans. A few clinics had recently invested in the equipment and trained staff. I tried to do a quick survey of medical schemes, to see how many of them would pay for scans. The results were patchy, but the main thrust was that this was new and expensive technology, and was not covered in current aid plans. One or two schemes were prepared to pay for scans if sufficient justification was provided by an oncologist.

Another unexpected problem appeared. Now, as you may be aware, a PET scan requires the injection of a radioactive substance into the blood stream. Generally this consists of a material with a very short half life, of the order of a couple of hours, and this means that it has to be prepared to order. The material is generally fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). The production facility cannot be too far aware from the clinic, because of the travel times.

In South Africa, the Medicines Control Council (MCC) regulates the performance of clinical trials and registration of medicines and medical devices for use in specific diseases. Apparently when the PET scan was introduced in South Africa, the early approval for irradiated FDG was on a temporary basis, and only a few hundred doses were approved. When these were used up by the clinics the process had to stop. Equipment which cost millions of Rands was sitting idle until the MCC got its act together.

I tried to find the cause of the problem. Enquiries to the MCC lead nowhere – they were not prepared to talk to me. And oncologists I spoke to just shook their heads and made vague comments about incompetence at the MCC. I got the impression that this was only one small example of a much more general problem.

After a couple of months the material was approved, and the PET scan could continue to be used, although the question of payment by medical aid funds was not resolved.

In August I received a document from my medical aid fund, explaining their new funding policy for PET scans. It appears that there are still concerns about the high cost of the technology, and there is “limited evidence on the clinical outcomes”. I would have thought that a sufficient body of knowledge has been developed, but No! Here in South Africa we apparently don’t believe anything unless we have proved it ourselves. The NIH syndrome (Not Invented Here) is alive and well!

Anyway, they have decided to run a pilot project for the next year. So, subject to some restrictions, they will now pay for PET Scans. Essentially, they will only pay for PET scans for melanoma patients in Stage III and Stage IV, for staging and re-staging, and monitoring of treatment.

Interesting that when I last saw my oncologist, before this new policy was published, he was not too concerned, and simply scheduled me for a chest xray, and ultrasound scans. He seemed to think that was quite satisfactory at this stage, and the plan is to only do another PET scan when I have completed the year’s interferon treatment.

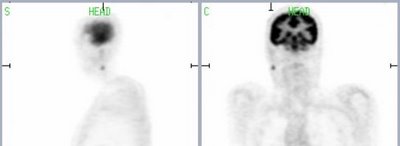

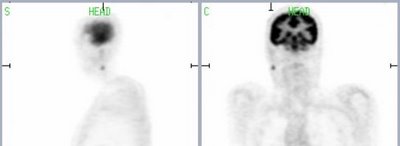

I received a CD with my original PET scan, and it contains the complete scan data and some software to view the data. I found the pictures it produced absolutely fascinating, but some people may not like to see everything that they reveal! Here are a few images which demonstrate what you get.

The little blip in line with the markers shows the parotid gland with melanoma.

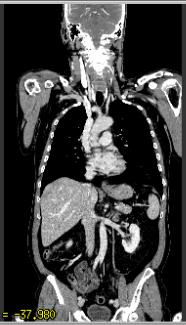

A general vertical slice, showing everything present and correct. (Well, not quite: My gall bladder was removed some years back. On some images you can see a couple of staples which were left after surgery!)

Here is another slice showing the affected gland.

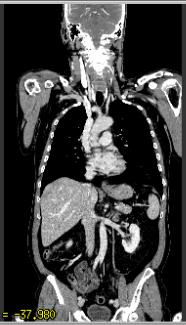

Darth Vader has nothing on this! These “rays” are caused by the large amount of metal in my teeth.

Although it is probably our most serious health issue, I won’t talk about HIV/AIDS in the South African context here. Perhaps another day…

When I was diagnosed with melanoma at the beginning of 2006, I was sent for a PET scan. At the time I didn’t know very much about it, but I quickly learned about the technology. But this did not prepare me for the actual experience, and I suddenly discovered how irrational feelings of claustrophobia could achieve a life of their own. I had to take a couple of additional tranquilizers to get through the process.

Another serious problem was the cost of the scan. This was about R12000 at the time (converts to about US $1600 at the official exchange rate). But the real challenge was that PET scans were not covered by my medical aid scheme. I could afford to pay this, but what about patients who are not so lucky?

A couple of months later, when I had come to grips with this melanoma creature, I did some more investigation into PET scans. A few clinics had recently invested in the equipment and trained staff. I tried to do a quick survey of medical schemes, to see how many of them would pay for scans. The results were patchy, but the main thrust was that this was new and expensive technology, and was not covered in current aid plans. One or two schemes were prepared to pay for scans if sufficient justification was provided by an oncologist.

Another unexpected problem appeared. Now, as you may be aware, a PET scan requires the injection of a radioactive substance into the blood stream. Generally this consists of a material with a very short half life, of the order of a couple of hours, and this means that it has to be prepared to order. The material is generally fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). The production facility cannot be too far aware from the clinic, because of the travel times.

In South Africa, the Medicines Control Council (MCC) regulates the performance of clinical trials and registration of medicines and medical devices for use in specific diseases. Apparently when the PET scan was introduced in South Africa, the early approval for irradiated FDG was on a temporary basis, and only a few hundred doses were approved. When these were used up by the clinics the process had to stop. Equipment which cost millions of Rands was sitting idle until the MCC got its act together.

I tried to find the cause of the problem. Enquiries to the MCC lead nowhere – they were not prepared to talk to me. And oncologists I spoke to just shook their heads and made vague comments about incompetence at the MCC. I got the impression that this was only one small example of a much more general problem.

After a couple of months the material was approved, and the PET scan could continue to be used, although the question of payment by medical aid funds was not resolved.

In August I received a document from my medical aid fund, explaining their new funding policy for PET scans. It appears that there are still concerns about the high cost of the technology, and there is “limited evidence on the clinical outcomes”. I would have thought that a sufficient body of knowledge has been developed, but No! Here in South Africa we apparently don’t believe anything unless we have proved it ourselves. The NIH syndrome (Not Invented Here) is alive and well!

Anyway, they have decided to run a pilot project for the next year. So, subject to some restrictions, they will now pay for PET Scans. Essentially, they will only pay for PET scans for melanoma patients in Stage III and Stage IV, for staging and re-staging, and monitoring of treatment.

Interesting that when I last saw my oncologist, before this new policy was published, he was not too concerned, and simply scheduled me for a chest xray, and ultrasound scans. He seemed to think that was quite satisfactory at this stage, and the plan is to only do another PET scan when I have completed the year’s interferon treatment.

I received a CD with my original PET scan, and it contains the complete scan data and some software to view the data. I found the pictures it produced absolutely fascinating, but some people may not like to see everything that they reveal! Here are a few images which demonstrate what you get.

The little blip in line with the markers shows the parotid gland with melanoma.

A general vertical slice, showing everything present and correct. (Well, not quite: My gall bladder was removed some years back. On some images you can see a couple of staples which were left after surgery!)

Here is another slice showing the affected gland.

Darth Vader has nothing on this! These “rays” are caused by the large amount of metal in my teeth.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home